Many historians and scientists regard the Western Europe, after the fall of the Roman Empire, as completely devoid of interest, a barren wilderness in the history of science. Contemptuously, they give medieval Europe the Dark Ages, and this epithet evokes pictures of filthy, illiterate peasants and rulers, with medieval society a pale, superstitious shadow of the Greek and Roman ages of reason and high philosophy.

The Dark Ages – Was Science Dead in Medieval Society?

With the aid of arrogant hindsight, the modern perspective of medieval society is of a war-torn and barbaric Europe. Poverty and ignorance replaced the great engineering works and relative peace of the Pax Romanum, and the controlling, growing church stifled development.

This view is biased and prejudiced, because the term ‘Dark Ages’ is simply means that there are few written records remaining from that era, especially when compared to the meticulous record-keeping and prolific writing of the Romans. The Middle Ages have very little evidence to support the idea that there was any progress in society during the periods 500 to 1400, and modern scholars regard the Golden Age of Islam and the enlightenment of the Byzantine Empire as the true centers of knowledge.

In the years immediately after the fall of Rome, there was a period of readjustment, where medieval society was more concerned with keeping peace and empire building than nurturing centers of learning. Despite this, Charlemagne tried to establish a scholastic tradition, and the later Middle Ages saw advancements in the philosophy of science and the refinement of the scientific method. Far from being a backwards medieval society, overshadowed by Islam and Byzantium, scholasticism acted as a nucleus for the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Early Medieval Society – The Dark Ages After the Collapse of Rome

The Early Medieval period, from about AD 500 to 1000, is regarded as the true Dark Ages, where medieval society slipped into barbarism and ignorance. There is some truth in this view, but even this era saw scientific and technological advances amongst the maelstrom of constant war and population shifts. This period was not a complete desert and, whilst we understand that raiding Saxons, Vikings, and other people halted progress, to a certain extent, there were still faint glimmerings that great minds were exploring the universe and trying to find answers.

|

| Theorica Platenarum by Gerard of Cremone. (Public Domain) |

In the west of the continent, where verdant Ireland meets the destructive power of the grey Atlantic, ascetic monks produced beautiful, vibrant illuminated manuscripts. In England, the Venerable Bede (672/673 – 735) meticulously recorded the Saxon Era during a time of raids from the fierce Northmen, bringing terror with their dragonboats. This English also created a fine book about using astronomical observations to calculate the start of Easter.

During this period, it is tempting to dismiss the Northmen as fierce, uncouth barbarians, forgetting that their famous longboats were marvelous feats of engineering, hundreds of years ahead of their time. The Vikings and the Saxons were capable of exquisite metalwork and metallurgy, with the fine swords and beautiful jewelry found in sites such as Sutton Hoo and Ladbyskibet showing that, even if the progress of empirical and observational science was slowed, craftsmen still pushed boundaries and tried new techniques. In this, they were undoubtedly influenced by ideas that filtered up the trade routes from Greece, Egypt, and even China and India.

The Norse sailors were master navigators and, whilst lacking compasses, could use the stars and a few instruments to navigate the trackless ocean to Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland. For those of us in Western representative republics, such as the UK, US, and Scandinavia, our political model and idea of Parliament or congress was built upon the Norse model.

Despite these advances, it is safe to say that the centuries immediately after the fall of Rome, from the 5th Century until the 9th Century, saw little progress in what we come to regard as the scientific method. Classical thought and philosophy were lost to the west and became the preserve of Islam and Byzantium, as an increasingly rural and dispossessed population began to rebuild after the collapse of Rome.

However, monastic study kept some of the scientific processes alive and, while most of their scholastic endeavors concerned the Bible, the monks of Western Europe also studied medicine, to care for the sick, and astronomy, to observe the stars and set the date for the all-important Easter. Their astronomy kept alive mathematics and geometry, although their methods were but an echo of the intricate mathematical functions of the Romans and the Greeks.

The Middle Ages – Charlemagne, Science, and Learning

|

| Charlemagne (Public Domain) |

During the 9th Century, these small embers of preserved knowledge leapt to life, as Western Europeans tried to systemize education; rulers and church leaders realized that education was the key to maintaining unity and peace. This period was known as the Carolingian Renaissance, a time when Charles the Great, often known as Charlemagne, tried to reestablish knowledge as a cornerstone of medieval society.

This ruthless emperor, often depicted as the Golden Hero of the Church, was a brutal man of war, but he was also a great believer in the power of learning. His Frankish Empire covered most of Western Europe, and he instigated a revival in art, culture, and learning, using the Catholic Church to transmit knowledge and education. He ordered the translation of many Latin texts and promoted astronomy, a field that he loved to study, despite his inability to read!

In England, a monk named Alcuin of York instigated a system of education in art and theology, and also in arithmetic, geometry and astronomy. Like the Carolingians, he began promoting the establishment of schools, usually attached to monasteries or noble courts. While the Carolingian Era was a pale reflection of the Classic Age, there were attempts to promote knowledge and the process only ended because of the breakup of the Frankish Empire after the death of Charlemagne, and a renewal of the barbarian incursions.

However, all was not lost, and some centers of learning clung stubbornly to scholarly pursuits throughout the political and social upheaval, forming a nucleus around which the First European Renaissance would grow. The teaching of logic, philosophy, and theology would fuel the growth of some of the greatest Christian thinkers ever seen, as Western European medieval society moved into the High Middle Ages.

The High Middle Ages – The Rebirth of Science and Scholasticism

This era, from 1000 until 1300, saw Western Europe slowly begin to crawl out of the endless warring, as populations grew and the shared Christian identity gave some unity of purpose, from the Ireland to Italy, and from Denmark to Spain. It is tempting to think of this era as a time of prolonged war between Christian and Muslim and, in Spain and the East, constant territorial bickering and the Crusades support this view.

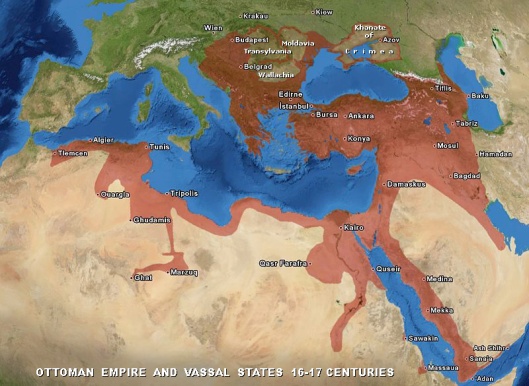

However, trade and the sharing of ideas were common, and merchants and mercenaries brought back ideas from Moorish Spain, the Holy Land, and Byzantium. The Muslims translated many of the Ancient Greek texts into Arabic and, in the middle of the 11th Century, scholars from all around Europe flocked to Spain to translate these books from Arabic into Latin. This provided a conduit for the knowledge of the Greeks to pass into Europe, where the schools set up by Charlemagne were now blossoming into universities. Many of these scholars, such as Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114-1187), learned Arabic so that they might complete their task.

By the 12th Century, centers of learning, known as the Studium Generale, sprang up across Western Europe, drawing scholars from far afield and mixing the knowledge of the Ancient Greeks with the new discoveries of the great Muslim philosophers and scientists. This blend of ideas formed the basis of Christian scholasticism and, whilst much of the scholastic school of thought turned towards theology, it also began to integrate scientific empiricism with religion.

This period may not have seen the great technological advances of the Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Persians, or Muslims, but the contribution of great thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Grosseteste, Francis Bacon, and William of Ockham to the creation of the Scientific Method cannot be underestimated.

Aquinas and Grosseteste – The Fathers of Scholasticism and the Scientific Method

|

| Thomas Aquinas, Painting by Benozzo Gozzoli (Public Domain) |

Thomas Aquinas, while more interested in using philosophy to prove the existence of God, oversaw a shift from Platonic reasoning towards Aristotelian empiricism. Robert Grosseteste, one of the major contributors to the scientific method, founded the Oxford Franciscan School and began to promote the dualistic scientific method first proposed by Aristotle.

His idea of resolution and composition involved experimentation and prediction; he firmly believed that observations should be used to propose a universal law, and this universal law should be used to predict outcomes. This was very similar to the idea of ancient astronomers, who used observations to discern trends, and used these trends to create predictive models for astronomical events.

Grosseteste was one of the first to set this out as an empirical process and his idea influenced such luminaries as Galileo, and underpinned the 17th Century Age of Enlightenment. However, his biggest influence was more immediate, reflected in the impact to the scientific method made by his pupil, Roger Bacon.

Roger Bacon – The Shining Light of Science in Medieval Society

|

| Roger Bacon, Statue in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. (Creative Commons) |

Roger Bacon is a name that belongs alongside Aristotle, Avicenna, Galileo, and Newton as one of the great minds behind the formation of the scientific method. He took the work of Grosseteste, Aristotle, and the Islamic alchemists, and used it to propose the idea of induction as the cornerstone of empiricism. He described the method of observation, prediction (hypothesis), and experimentation, also adding that results should be independently verified, documenting his results in fine detail so that others might repeat the experiment.

With a nod towards the Islamic scholars, such as Ibn Sina ands Al-Battani, any student writing an experimental paper is following the tradition laid down by Bacon. Both Bacon and Grosseteste studied optics, and Bacon devised a plan for creating a telescope, although there is no evidence to suggest that he actually built one, leaving the honor to Galileo. Bacon also petitioned the Pope to promote the teaching of natural science, a lost discipline in medieval Europe.

The Late Middle Ages – Scholasticism and the Scientific Method

|

| Robert Grosseteste – 13th Century Image (Public Domain) |

The Late Middle Ages, from 1300 until 1500, saw progress speed up, as thinkers continued the work of scholasticism, adding to the philosophy underpinning science, Late Middle Age made sophisticated observations and theories that were sadly superseded by the work of later scientists.William of Ockham, in the 14th century, proposed his idea of parsimony and the famous Ockam’s Razor, still used by scientists to find answers from amongst conflicting explanations. Jean Buridan challenged Aristotelian physics and developed the idea of impetus, a concept that predated Newtonian physics and inertia.

Thomas Bradwardine investigated physics, and his sophisticated study of kinematics and velocity predated Galileo’s work on falling objects. Oresme proposed a compelling theory about a heliocentric, rather than geocentric, universe, two centuries before Copernicus, and he proposed that light and color were related, long before Hooke.

Finally, many of the scholastic philosophers sought to remove divine intervention from the process of explaining natural phenomena, believing that scholars should look for a simpler, natural cause, rather than stating that it must be the work of divine providence.

The Black Death – The Destroyer of Medieval Society and Scholasticism

It seems strange that the advances of many of these philosophers and scholars became forgotten and underplayed in favor of the later thinkers that would drive the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment. However, the first Renaissance of the Middle Ages was halted by a natural phenomenon, the Black Death, which killed over a third of Europeans, especially in the growing urban areas.

The mass disruption to medieval society caused by the plague set the progress of science and discovery back, and the knowledge would not reemerge until the Renaissance.

Was Science Important to Medieval Society?

In Western Europe, the centuries immediately after the collapse of Rome saw huge socio-economic upheaval, barbarian raids, and the return to a rural culture. However, we must be careful not to label the entire medieval period as the Dark Ages. The High and Late Middle Ages may not have rivaled the Classic Age or the later Renaissance in scope, but they saw the growth of empiricism and the scientific method.

The development of scholasticism lay in stark contrast to the Hollywood films that depict the era as filled with superstition and the dictatorial control of the church. Medieval society saw Christian philosophers make reasoned arguments, showing that there should be no conflict between the Church and scientific discovery, and many of their theories formed the nucleus of later discoveries.

The Middle Ages saw the growth of the first universities, and the development of the scientific method. It is certainly fair to say that the Rising Star of Islam and the Golden Walls of Byzantium were the true centers of learning, with scholars flocking to Moorish Spain, Byzantium, or the houses of learning in Baghdad.

This does not mean that medieval Europe was a superstitious backwater, and great minds, influenced by the Muslim philosophers and the translation of the work of the Greeks into Latin, developed their own ideas and theories, many of which underpin modern scientific techniques.The great cathedrals of the age, the formation of universities, the contribution of scholasticism to the philosophy of science and logic, showed that medieval Europe was not a poor relation of the East.